The people who use our boards.

390 interviews since 2018

Scott

Morse

Senior Software Engineer | Musician

Who are you, and what do you do? What do you like to do outside of work?

My name is Scott Morse, like Morse code, though I only learned to code later in life, feeling almost like I was doomed to be a software engineer.

My first main passion was, and still is, music. I studied jazz and classical music, with guitar as my primary instrument. After my studies in college, I lived completely off of music for a while, gigging on weekends and teaching up to forty music students during the weekdays. Later, I worked on cruise ships as a sight-reading guitarist for a year, meaning I read new sheet music daily and played a variety of styles every week.

During my time working on the cruise ship, I started to learn how to code, at first out of pure curiosity, but I quickly found that I truly enjoyed it, and it's no coincidence it became a secondary passion. I took a four-month coding boot camp course after some months of learning Python on my own. Since then, I have worked for various companies, from the startup to enterprise, primarily in the education and music industries, starting first as an intern and later waking up one day as a technical lead engineer for a multibillion-dollar company. Now I've taken a step back from the corporate world for more of my own independent pursuits.

Over time, I've learned that there are compelling parallels between musical composition and the composition of code. Music theory is often literally called "codified music" by academics. Sheet music is an abstract language of instructions meant to be executed in order by a musician, while code is also an abstract language of instructions to be executed in order by a computer.

I say that all software engineers are "sight-readers" in the same sense that a number musicians are with sheet music, in that we must be able to comprehend the code we read quickly in order to work efficiently enough with it. There is a two-way street then between the writer and reader, where the writer must set the reader up for success, and the reader must practice literacy in the language. This is, at least, the ideal situation for everyone to have a good time.

Despite the nonhuman nature of computer technology we are well aware of, code is designed for human beings to read and write, or otherwise, we'd just use binary directly. The practice of writing and reading code is still therefore very much a human activity, a relatively new use for the language center of the brain.

It might not be a surprise that I live a lot in my head with these geeky pursuits. However, to play the guitar or to type code requires heavy use of my hands. At times, I've struggled with tendinitis in my arms and anxious trips to the hand doctor to check for carpal tunnel. While my Moonlander setup plays a part in my solution for this by providing me with ideal ergonomics and shortcuts, a lot more goes into play to keep myself healthy in my pursuits. About a year ago, I started to heavily get into the practices of yoga and Alexander Technique in order to attempt to correct issues with my posture and muscular tension that are common among most people these days but were clearly causing me specific issues due to my hand-heavy obsessions.

Yoga has quite literally helped me bring more balance to my body and mind while strengthening postural muscles and arm muscles that support the hands, and there is growing evidence that improving your sense of balance can directly affect even your mental health, perhaps allowing us to abstractly balance our lives better, similarly to how we use more primal neural circuitry like fight-or-flight to manage purely abstract threats in our imagination, for better or for worse.

If we consider that the head is as heavy as a bowling ball, then simply holding it a bit out of balance means that your small neck muscles are going to work very hard to hold it up, just like holding a bowling ball out with your fingers would tire and stress your arms. The balance of the head and torso are a keystone of both Alexander Technique and yoga. My neck tension clearly had been snowballing all the way to my arms and hands and more.

A perspective shift that was important to me is that when we type, play the guitar, knit a funny sweater for a friend, or knead dough for a strudel, we are not "just using our hands," but we are always using the entirety of our body and mind to perform these actions, and to neglect this is ultimately to our hands' detriment. In yoga, we have the term āsana, simply meaning "posture," including postures such as the Downward Facing Dog (Adho Mukha Svanāsana) or Locust (Śalabhāsana). In practice, yoga teachers explore a variety of āsana, sometimes creatively, using postures that don't always have a strict definition. My personal perspective on āsana is that it represents the set of all healthy positions you can make with your own body, which is why everyone's yoga practice differs. When simply thinking of it this way, I think it's easy to see why strengthening your ability to hold yourself in a variety of possible positions healthily is good for both the body and mind.

Similarly to how we can place our bodies in a variety of postures, when we type or use any hand instrument, we also place our hands in a variety of mini āsana, our hands stretching or bending fingers in a variety of postures of their own, including the hand positions for Vim typing, different guitar chords, paintbrush techniques, and the like.

My main drive in life at this time is to further integrate these three main domains that I pursue self-improvement in: music, technology, and the use of my body and mind through yoga. And if possible, I'd like to remain healthy in body and mind in doing so, as it can be a struggle to find balance between my interests. I have to thank ZSA for inventing tools that assist me on several levels in these pursuits.

What hardware do you use?

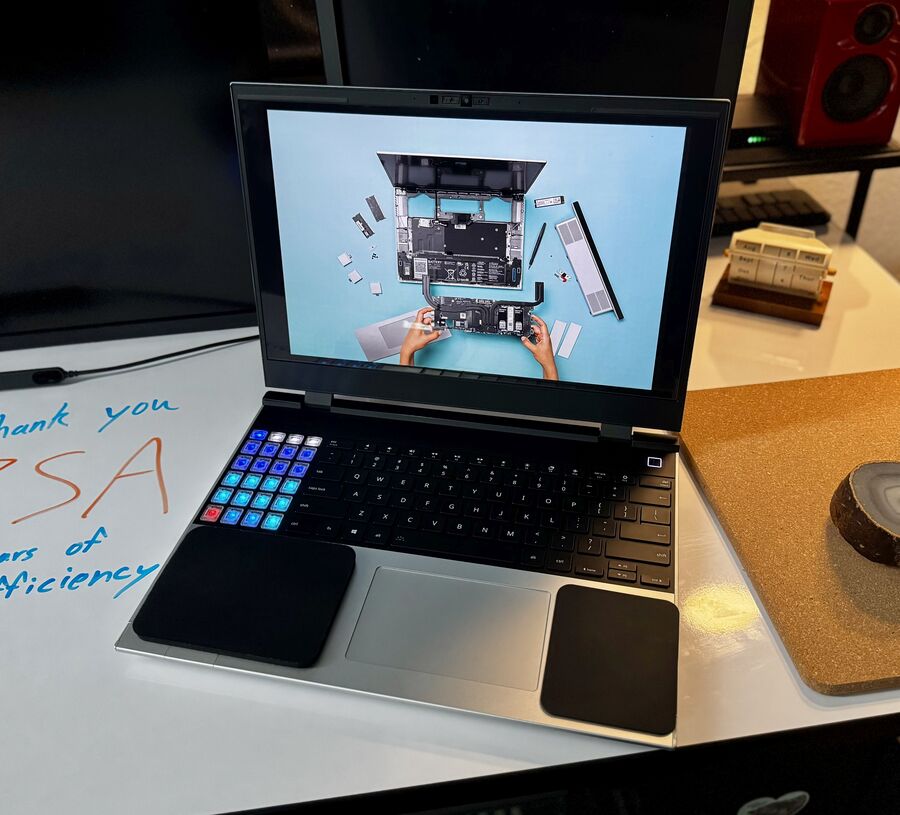

My main workstation computer is a desktop PC I built myself, nicknamed Moo Deng after the famous baby pygmy hippo who was viral at the time, and is similarly fast, thick, and dark grey. Conveniently, I had recently purchased a special edition Moo Deng: Full of Rage guitar distortion pedal from 1981 Inventions that came with a custom sticker I donned on the front of my PC case. This is the machine I primarily use my Moonlander on.

My standing desk itself is an important tool, made by the company UPLIFT out of Austin, where I was living when I got it, so my custom desk arrived in only two days after order. The entire top of the desk is whiteboard, which I use to take notes, make to-do lists, or work out and diagram solutions to software problems. I can slide an Egofit treadmill easily underneath, which I use most often while playing games like Balatro with a wireless controller.

For audio, I currently have the EVO 4 interface, which allows me to use microphone inputs with phantom power and has a dedicated guitar input so that I can record directly in, or with my Line 6 Helix digital effects station.

I also have a Framework 16-inch laptop, a modular laptop that allows for the replacement of just about any critical part. I've been highly satisfied with this machine and write my own QMK firmware, the same keyboard firmware ZSA's Oryx builds on top of, for the macro pad on-board.

On both machines, I run Arch Linux, using the KDE Plasma desktop environment. This has been my favorite operating system setup for several years now.

In the photos, you may see one of my Tidbyt devices, a small screen that can run simple apps written in a Python-like language. I mainly have it for fun, and it also happens to perfectly hold up a monitor that's a bit heavy for its arm.

And what software?

As I said earlier, I am primarily an Arch Linux user using KDE Plasma for my desktop.

On my PC, I even run custom KWin scripts that give me fine-grained control of window management, using my still prerelease (at the time of writing) open-source project kwin-ts that lets me write KWin scripts in TypeScript rather than JavaScript with relatively accurate runtime types.

For my command line, I use the Z shell (zsh) primarily with the Zellij multiplexer.

My primary coding language is TypeScript, and naturally my main IDE is then Visual Studio Code. Vim is my primary shell-based editor, and I use the Vim extension for VSCode. While not a Vim superuser, I take advantage of certain shortcuts and tend to use a hybrid modern/traditional approach to development, trying to be strong with my command line but willing to use a more modern graphical interface if I like it enough, especially since my hardware can handle about any workflow.

I tend to approach guitar similarly, using a hybrid fingerpicking technique based on classical, blues, and country/bluegrass styles, and the style in which I write TypeScript can also appear as a nondogmatic hybrid of functional, procedural, and object-oriented patterns.

When it comes to developing in TypeScript, I prefer to use the newer Bun runtime for its speed whenever I can, whether for scripting or building React apps. I have yet another early-in-the-works open-source project, bun-workspaces, for providing more features on top of Bun's monorepo capabilities.

I enjoy using Obsidian for note-taking with Markdown syntax and having secure sync between my devices.

I'm also versed in Talon, the developer-friendly accessibility software for voice commands. I learned to use this after my last case of tendinitis, and at my peak of practice I could demonstrate to coworkers how to write a simple React web app without ever touching my keyboard, using the Cursorless VSCode extension, which works with Talon for hands-free voice coding.

I do not use Talon to nearly that extent regularly, but I have found that even outside of injury or other accessibility reasons, voice commands can be inherently very intuitive and quick to remember and use. I often develop using a hybrid of Talon commands and Moonlander shortcuts, picking whichever feels easiest.

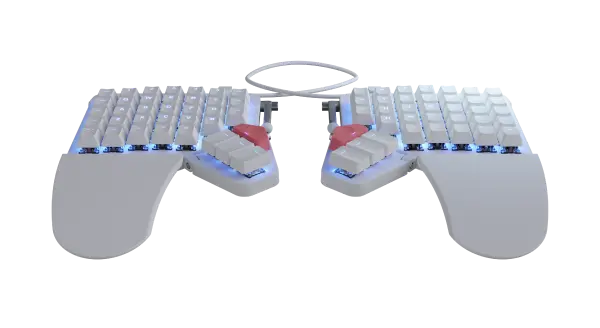

What’s your keyboard setup like? Do you use a custom layout or custom keycaps?

My friend Cole sent me a link about the Moonlander after he discovered it, and upon learning that it could be mounted to my chair arms, I had to try it. I had only used run-of-the-mill keyboards prior to this, but as I matured as a developer, I realized that in the same way the quality of my equipment is important for music, it's also important to have an ideal instrument for my computer.

While I wasn’t yet into yoga or similar practices, I instinctively knew that being able to sit with my shoulders fully retracted in my chair would likely be better than the constant protraction most of us find ourselves in, causing tension and postural collapse at our neck and shoulders.

I have spent the equivalent of many workdays, possibly even work weeks, configuring my Moonlander's settings and shortcuts. ZSA reached out to have me create a tour for my layout.

I still use the QWERTY layout, since it was drilled into my head from an early age, but I have moved around several of the default Moonlander key positions based on my needs. I have a “mouse” in my right hand, grouping all mouse-related operations in the thumb keys and bottom row. I have a backup mouse tucked away on my desk, but I primarily use the keyboard mouse controls.

I use the Cherry Silent Red switches after having tried very clicky switches for a while, and there are individuals in my life who would disagree with this, but I enjoy the subtle smooth quiet motion, even if they aren't theoretically the best for what I use them for primarily. Despite what you may assume based on the rest of my writing, I'm not actually very particular about mechanical keyboard details such as these (yet).

My configuration contains a large number of shortcuts for the browser, desktop window management, launching applications I use commonly, my terminal shell, VSCode, and more. I have a fun mode that I can activate for using the musical buzzer mode that is available on the keyboard, which turns the keys into a chromatic scale, and for a while I thought I might try to learn “Flight of the Bumblebee” arranged for the ZSA Moonlander, but I haven't followed through on that (yet).

What would be your dream setup?

I am a big fan of having a lot of screen real estate. I already have my four-monitor setup that takes up nearly my whole visual field with two stacked monitors and a vertical monitor on each side, which are ideal for horizontally compact long text.

I use all these monitors regularly, especially when I am developing, and I even further use my KWin scripts to grid and tile windows in various layouts within each monitor, and I further take advantage of several virtual desktops I can swap between for another high level of window grouping. The only reasons I don't have more monitors are hardware limitations and practicality.

Because of this, I have a fantasy of the future of AR, where screens can all be virtualized by something like AR glasses, so that perhaps an office would only need to have a variety of blank white shapes upon which screens can be dynamically rendered as needed.

This could allow for a variety of creative new shapes for interfaces that wouldn't be possible with physical monitors, and screen real estate would be much more scalable without as much physical limitation and cabling. I say this as a frontend-leaning web developer, so some might consider me a traitor to my own kind for wanting an increase in the number of different screens we'll have to consider.

I don't know how soon or viable this future is, but I am already this far in my mad-scientist/pretend-space-captain setup that spawned merely from the desire to enhance my productivity without hurting my hands, so I might as well take it to the next stage once possible.

Portrait photo credit: Emilio Mesa